Introduction

Fukuoka, at the southern end of the Shinkansen high speed rail, is one of Western Japan’s most rapidly growing cities and increasingly important as a gateway to the rest of Asia.The Nanakuma Line, opened in 2005, connects downtown Fukuoka with the southwestern area of the city. The Line consists of sixteen stations, newly designed rail cars, and associated ventilation and maintenance facilities.

Design and construction of the line occurred over a ten-year period and included a complex and extensive participatory process that involved citizens with a wide range of ages and abilities. Surveys and focus groups included older people, pregnant women and adults and children with disabilities. The result offers a model of a subway system that is comfortable, intuitive and understandable to local residents and visitors from Japan and abroad.

Description

Fukuoka is located in southern Japan on Hakata Bay and edged with wooded hills with a temperate climate. The city covers 340 square kilometers and is home to approximately 1.4 million residents. The growing city’s southwestern area, with easy access to the sea and mountains, has experienced extensive residential development.

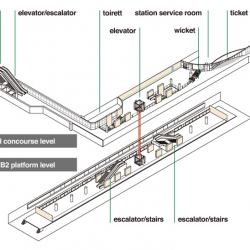

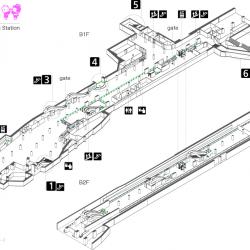

The Nanakuma Subway Line connects this area with the downtown core and the City’s two other subway lines, the Kuko and Hakozaki lines. The Nanakuma Subway Line is approximately 12km long, completely underground, uses a 1,435mm gauge of track and automatic train control signal system. Tunnel boring machines created the tunnel path. They used cut-and-cover construction for the sixteen stations along with the ventilation and transformer stations. The line is serviced by the Hashimoto yard consisting of approximately .7km of track and various maintenance buildings. The city paid two-thirds of the 280 billion yen cost of the line with one third split between the prefecture and national governments.

The commitment to user-centered design began at the conceptual design stage and heavily influenced station design. Focus groups identified their preference for universal design, day-lighting, legible uncluttered station layouts. Navigation within stations is attentive to clear lines of sight as well as the natural “desire lines” in which people opt for the shortest and most efficient route to where they want to go. In keeping with the preference for natural light, station use extensive glass in key areas like entrances and exits.

Photos

Terminus Station

Subway Platform

Train Threshold

Fare Gates

Station Symbols

Simple Floor Plan

Detailed Floor Plan

Subway Car Interior 1

Subway Car Interior 2

Elevator on Platform

Fare Vending Machines

Stairs and Escalator

Lobby Hallway

Design and the User Experience

The Nanakuma line set a priority on creating a welcoming and easy-to-use environment across a wide spectrum of users including children, older people, people who are directionally challenged or foreign visitors who do not read Japanese. Designers were especially attentive to creating features that accommodated physical, sensory and cognitive limitations. The project represents both the evolution and sophistication of thinking about the role of design in creating a more equitable society responsive to changing demographics. Full inclusion and independent social activity by older people, people with disabilities and women have become a pervasive cultural value.

The same year that the Nanakuma line opened, 2005, the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MLIT) established a universal design policy for public facilities and places. The new universal design policy acknowledged the progress of barrier-free policies but criticized the narrow emphasis on accommodating the needs of people with physical functional limitations and noted that information and psychological barriers remain. The new guidelines promoted public transit as a priority and user participation in design as central to achieving effecrtive universal design that extended beyond the more limited concerns of barrier-free.

User engagement began at conceptual planning and schematic design with a level of commitment that set a new standard for the engagement of user/experts in Japan. They orchestrated outreach to groups unlikely to have come forward independently: pregnant women, frail elders, children, people with vision impairments, people with hearing loss, people with cognitive impairments, and people with mobility impairments. A general vision for the new line emerged from dozens of meetings, questionnaires and focus groups: Stations with high mobility, easy utilization and information that can be easily understood by everyone. Specific defining characteristics of the new line were also generated:

- Brighter stations with daylight

- Open spacious areas

- Easy-to-use features

- Easily-understood information

These desired characteristics drove the design of station headhouses, lobbies and platforms. Everyone uses the same easily recognizable entrances whether arriving at street level by bus, foot, or bike. The entrances have tactile maps and guidance strips that lead to the stairs ad directly adjacent elevators. Each station has indoor bicycle parking. Once at lobby level, riders experience clear sight lines as well as perceptibly higher light levels in key areas such as the fare gates and at decision points along the path of travel. Railings and tactile guidance strips can be used for navigation into the station and down to the platforms. In response to a commitment to improve the transit experience for people with sensory limitations, talking signs using Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) technology are integrated into the station’s system for navigation. Fare machines are easily accessed whether standing or seated, tall or short.

Positioned in relation to movement desire lines, the fare gates are long and wide enough to accommodate people assisting children or frail elders. Escalators and elevators connect to the platforms. Escalators automatically shut off when not in use and sound an alert if someone tries to go down an up escalator. Elevators are large, feature extensive glass, offer multiple control panels for easier access and automatically travel between floors. Elevators’ home floors are programmed to reflect the natural flow of passengers throughout the day and minimize wait time and energy use. A recorded voice announces arrival floors.

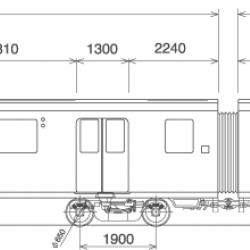

At platforms, extensive uncluttered line and system maps clearly convey critical information to riders. Symbols are used extensively and individual stations have unique icons to simplify wayfinding and orientation. Line maps note the average amount of time from one station to another. Train arrival information is provided on visual messaging screens. Glass barrier walls at the platform edge prevent falls into the track bed and enhance safety generally. Upon train arrival, the doors open on both the train and the platform with an audible tone. Trains were designed in conjunction with the tracks and platforms so there are virtually no horizontal gaps and minimal vertical gaps.

Critical station equipment such as heating, ventilating and air-conditioning (HVAC), fire hose connections and utility chases are well integrated into the structures with minimal visual impact. They pose little distraction or hazard to riders. There are dedicated locations for advertisements.

Evaluation

The Nanakuma Subway Line set a new global standard for inclusive subway design. The investment in participatory planning and the engagement with user/experts is unrivalled. Leaders invested in learning about impediments to use for people with physical but also sensory and cognitive issues and designed the environments to be welcoming and usable by everyone. Considerations for usability extended to foreign visitors who could not read Japanese.

On element of Nanakuma’s recipe for success was the integration of multiple disciplines on the planning and design team which included civil engineering, architectural design, product design, graphic design and other elements of the total design and construction package. This group was responsible for design evaluation, and included people from Kyushu University, top managers from Fukuoka City government as well as hundreds of citizens. Organizations of people with visual and hearing impediments have complained that placement of advertising is still not controlled enough to prevent visual confusion and that it conflicts with wayfinding cues. It’s unclear whether the excellent management of the platform gap in either direction will remain stable or become larger as time and wear take their toll on the trains and track.

Universal Design Features

- Extensive participatory process with use/experts to design various building elements including entrances, toilet rooms, elevators, stairs, lobbies

- Tactile maps at station entrances, lobbies and platforms

- Detectable guide strip from each station entrance to lobby, fare gates and down to the platforms

- Elevators with multiple control panels, automatic operation and home floors programmed to correspond with daily use patterns

- Escalators that alert people with visual impairments that they are reaching the end

- Visual and audio next train announcements

- Lighting levels vary in relation to function of the area

- Restrooms are all accessible to wheelchairs users, make extensive use of automatic sensor functions to maximize ease-of-use and minimize bacteria, are large enough for a helper to assist and have changing tables.

Environmentally Sustainable Features

- Maximum use of daylighting

- Escalators that shut off when not in use

- Sensors activate flushers, faucets, soap and towel dispensers in the toilet rooms for energy saving

Project Details

Location: Fukuoka Prefecture, Kyushu, Japan

Completed: 2005

Client: Fukuoka City Transportation Bureau

Project Team

Project Manager:

- Toshimitsu Sadamura, GA-TAP. Inc

Planning Team: (Japan Sign Design Association design committee)

- Tatsuzo Akase/ rei design & plannings

- Toshimitsu Sadamura/ GA-TAP. Inc

- Masato Hirotani/ GA-TAP. Inc

- Yasuo Yokota/ GK Graphics Incorporated

- Masaru Sato/ Kyushu University

- Hisayasu Ihara/ Kyushu University

- Miyazawa/ GK Sekkei Incorporated

Architect Design Team

- Masato Hirotani

- Makoto Ito, Yoshihikjo Ooki, Kenji Tojima, Yoshitaka Nishizono, Dai Higashigawa/ GA-TAP. Inc

- Shoei Yoh/ Yoh Design Studio?

- Yasuo Katakura/ rei design & plannings

- Akira Kitagawa, Akihiko Fukagawa, Kazuya Morita/ NIKKEN SEKKEI

- Junko Okabe/ Can Design Corporation

- Hidetoshi Ryu/ Networks Hidetsugu Iwamatsu, Naoyuki Seki, Yoshitaka Tanaka, Shingo Harada, Hiromitsu Hirashima, Hiroshi Wakayama / General Asahi Co., Ltd.

- Kenji Nakano/ Kei Workshop?

Sign Design Team

- Makoto Hayata, Hirohisa Matsunoo, Takashi Yamada/ GA-TAP. Inc

- Maya Nakamuta/ MED

- Kozo Maeda/ EXBEC CORPORATION

Furniture Design

- Kouji Umemoto, Akira Tokunaga/ PA Design, Inc

Communication Design Team

- Mariko Okabe, Akira Takaki, Hideyuki Nishito, Toshiharu Nishimura, Yuko Noda,yurika Moriyama/ GA-TAP. Inc

- Hajime Inoue/ Brook Studio

- Masakatsu Mitoma/ Mitoma Photo Studio

Design Committee

- Masaru Sato/ Kyushu University

- Tomoki Kawachi/ Kyushu Sangyo University

- Izumi Shibata/ Shibata Izumi Archit

- Terukazu Takeshita/ Kyushu University

- Miki Matsushita Lighting Design Co., Ltd

- Kiyohimi Kikutake / sculptor

- Miyuki Tanimoto/ Copy writer

Additional information

Awards

- Barrier-Free Contributor's Award Prime Minister's Award

- Cabinet Office SDA Minister of Economy

- Trade and Industry Award SDA Japan Sign Design Association Grand Award

- Good Design Award

- Illuminating Engineering Institute of Japan Award

- Association of Railway Architects Prize

- Machine Design Award

- Fukuoka Urban Scenery Award

- Fukuoka Ad Association Prize

Funding By

Propose a Case Study

Help us improve our Case Study library